news article

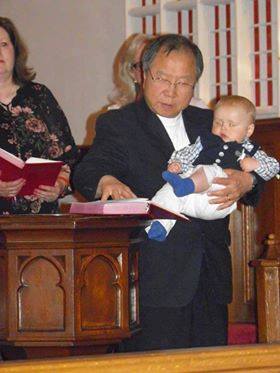

Being a Korean Pastor in Caucasian Congregations

July 13, 2021 / By The Rev. Dr. Moon Ho Kim

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2021 Issue 1 of the Advocate, which focused on the theme “Celebrating who we are.” Click here to access this issue.

One day I went to a restaurant to have dinner soon after I came to this country more than four decades ago. A waitress came to take an order, "What would you like to have for dinner?" I chose one among the steaks in the menu. But it was not easy to order the steak dinner because of many questions following one after another. "How would you like to have the steak done?" asked the waitress. I couldn’t understand what she meant, "Excuse me, what did you say?" "How would you like to have your steak done? Rare, medium or well done?" "Well, I don't know. What is rare and medium?" I replied. For it was the first time I ordered a steak dinner in this country, neither had I ever dined out in any American restaurant before even in S. Korea. "It's up to you,” I retorted, “Please bring whatever you feel like bringing. I just want to eat a steak for dinner this evening." "Okay! I will," she said.

But she asked me again, “How would you like to have your potato?" At the moment, I was a little irritated. I was not used to answering those questions. "What do you mean?" I asked the waitress. "How would you like to have your potato? French fry, mashed potato or baked?" "I'm sorry. I really have no idea. Would you please choose one of them for me? And, please don’t ask me any more questions." I heaved a sigh of relief, thinking all her questions were over. She was, however, still standing beside me for another question: "What would you like to choose among these side dishes: green beans, carrots, coleslaw, or cottage cheese?" You know what my answer was. "I really don't know. It's totally up to you." She said with smile, "Okay!" Yet, she kept torturing me with the next question, "What kind of salad dressing do you want? We have Italian, French, and Russian dressing." "I don't know. I’ve never tasted those dressings in my life. Bring any dressing you like to recommend." "Okay! I will," she replied.

But she didn’t leave me alone. "Sir, I’m sorry for bothering you again,” said the waitress, “I have the last question to ask. ‘What drink would you like to have?’” “Coffee, please,” I articulated my answer; it was the only question I could understand and with it I thought all the torturing time was over. However, my guess was not right. “What coffee would you like to have, caffeinated or decaffeinated?” she continued. “Caffeinated,” I replied, wondering what it really means. Anyway, I was feeling relieved to give her a straight-forward answer for the first time. But it was not long before she was asking again, “Do you want sugar and creamer for the coffee?" "Yes, please!" Along with this answer, the waitress folded her orderbook and walked away from me. I was feeling like the student who came out of the classroom after finishing the important exam. That was a quite experience I had in the American restaurant right after I came to this country, and the funny episode is still lingering in my head even after four decades passed by.

The reason I opened this article with my funny experience is to tell you that one of the great luxuries we enjoy in this country America is the luxury of choice, sometimes, too many for us to get unspoiled. Yet, we Korean-American pastors and their spouses raised in Korean culture are not accustomed to this American culture in which many choices or options are offered to choose. In Korean culture, as children, we got well oriented to adapt whatever parents decide for us in our behalf and follow it without thinking any other options to choose. Even during our adolescence, we had no other choices but to focus on studying hard in school in order to enter one of the top universities in S. Korea. If we chose some other option such as dating with a girlfriend during high school days, they feel that they already become a loser in competition with other friends and classmates.

But you know what? Such a different cultural background has turned out beneficial later as we develop our pastoral leadership in the cross-cultural ministry,  particularly, in Anglo-American parishes where many options and choices are tempting people to go astray from God. For instance, one of the issues most Korean-American pastors are struggling with is how to understand the parishioners who scarcely come to church to worship Sunday morning but faithfully show up in other church activities like church dinner sales and community events. Korean-American pastors think it is not option but a basic duty to go to church Sunday morning and worship the Lord like good students who never think it optional to go to school every day.

particularly, in Anglo-American parishes where many options and choices are tempting people to go astray from God. For instance, one of the issues most Korean-American pastors are struggling with is how to understand the parishioners who scarcely come to church to worship Sunday morning but faithfully show up in other church activities like church dinner sales and community events. Korean-American pastors think it is not option but a basic duty to go to church Sunday morning and worship the Lord like good students who never think it optional to go to school every day.

It has been almost four decades since I started a full-time parish ministry as an ordained clergy in the United Methodist Church, and in the end of June this year 2021, I’m planning to retire from my ministry. Prior to it, I would like to take this opportunity to share with you two major issues I’ve been thinking of, particularly, as one of the Korean-American pastors serving in the cross-cultural ministry.

First, prejudice was a stumbling stone in my parish ministry like most ethnic-minority pastors are experiencing. It’s obvious that prejudice is very common and universal in everyone’s life, yet the war against prejudice is never-ending, particularly, in the context of cross-cultural ministry. Because of a different culture and language barrier, Korean-American pastors sometimes have to face a negative attitude from some of their parishioners and community people as well. Their unfavorable feeling formed beforehand without knowledge about us leads our ministry to unnecessary conflicts mainly in the area where not many parishioners have an opportunity to see foreigners in their community. Many people call it racism, but racism is derived from people’s mind filled with prejudice, which is the preconceived perception toward a different person with a different skin color and different language.

Yet, throughout ministering to several Caucasian congregations I came to acknowledge such a negative perception was gradually melting away as time, went by, particularly, when working together with them as their pastor. The more often I spent time with them, the more quickly their prejudice was gone. Otherwise, I would not hav e continued my cross-cultural ministry even a year. To the contrary, the people who had resisted me at first have eventually turned out to be the most friendly and closest to me by the time I leave their churches.

e continued my cross-cultural ministry even a year. To the contrary, the people who had resisted me at first have eventually turned out to be the most friendly and closest to me by the time I leave their churches.

I appreciate that most Methodist lay leaders and congregations are so open-minded, kind, inclusive, and embrace their Korean-American new pastor each time I was appointed to new parishes. It was totally God’s grace that I was able to serve the Lord with such wonderful and gracious Methodist people throughout the whole years of my ministry despite cultural and language barriers between.

The different spiritual background most Korean-American pastors have is another contributing factor to managing their cross-cultural ministry comparatively well. In general, they’ve grown in the conservative and spirit-filled Christian community in S. Korea or Korean-American immigrant community in this country. Accordingly, most of them have a worship-centered, Bible-centered and Christ-centered faith in addition to their strong financial supports for global missions. Amid the secularization of Christianity of this day, they keep striving hard to hold a Judeo-Christian value and witness for it through their ministry. Despite cultural and language barriers, they endeavor to spread the Gospel about Jesus and the kingdom of God as the Apostle Paul did in no matter what different circumstances in culture and language during his missionary journey in the first century. When we study the Book of Acts, we realize how powerful Paul’s cross-cultural ministry was wherever God moved him from one place to another mainly in the pagan world.

Here in the cross-cultural context, one element contributing to Paul’s powerful and fruitful ministry was not only his fluent bilingual speaking of Hebrew and Greek languages but the sincere image he planted in the minds of people living in a different culture, tradition and language. The same is true of most Korean-American pastors serving in the cross-cultural ministry. Since English is not their native language, it is not easy to speak as good as their parishioners do. Nevertheless, they show their sincere and faithful heart in the parish ministry and keep striving hard to fulfill their important role as a spiritual leader. I’ve perceived throughout all my cross-cultural parish ministries how true it is that our fruitful ministries are not produced out of fluent speaking of language but rather on our sincere heart and dedicated spirit to people in need of our care and God whom we love to worship faithfully as well.